- info@aromantique.co.uk

- 07419 777 451

Heather Dawn: Godfrey. P.G.C.E., B.Sc. (Joint Hon)

According to a Survey carried out by The Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD) (October 2011), “stress has become the most common cause of long-term sickness absence for both manual and non-manual employees”. The Health and Safety Executives (HSE) ‘Self-Reported Work-Related Illness and Workplace Injuries Labour Force Report’ (2010/2011) indicates that work-related stress, depression or anxiety accounted for an estimated 6,214,000 days off work and musculoskeletal disorders accounted for a further estimated 6,245,000 days off work; a total of more than twelve and a half million working days lost. MIND (2012) reiterate this estimate, stating that “70 million working days are lost every year due to mental ill health, with 10 million working days directly caused by work-related problems”, costing an estimated £26 billion a year through sickness absence and lost productivity.

According to a Survey carried out by The Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD) (October 2011), “stress has become the most common cause of long-term sickness absence for both manual and non-manual employees”. The Health and Safety Executives (HSE) ‘Self-Reported Work-Related Illness and Workplace Injuries Labour Force Report’ (2010/2011) indicates that work-related stress, depression or anxiety accounted for an estimated 6,214,000 days off work and musculoskeletal disorders accounted for a further estimated 6,245,000 days off work; a total of more than twelve and a half million working days lost. MIND (2012) reiterate this estimate, stating that “70 million working days are lost every year due to mental ill health, with 10 million working days directly caused by work-related problems”, costing an estimated £26 billion a year through sickness absence and lost productivity.

The Department of Work and Pension’s ‘Health, Work and Well-being: Base Line Indicators Report’ (2010) acknowledges that “the majority of employers agreed there was a link between work and the health and well-being of their employees and that they have a responsibility to encourage employees to be physically and mentally healthy”. This Report also indicates that the majority of working age adults recognise that work can have a positive impact on health with over eight in ten respondents of their survey suggesting “that paid work was generally good or very good for both physical and mental health”.

Stress can be both negative and positive. Hans Seyle (1907 – 1984) explored the effects of stress on the human organism and discovered that psycho-emotional stress is influenced by a person’s perception, or attitude. He identified two types of stress, eu-stress which acts as a positive drive or motivator and dis-stress which triggers a negative, potentially debilitating psycho- emotional and consequently physiological negative reaction which can lead to dis-ease (Ryan 2004). The CIPD acknowledge, in their fact sheet “Stress and Mental Health at Work”, that: “there is sometimes confusion between the terms pressure and stress. It is healthy and essential that people experience challenges within their lives that cause levels of pressure and, up to a certain point, an increase in pressure can improve performance and the quality of life. However, if pressure becomes excessive, it loses its beneficial effect and becomes harmful and destructive to health.”

Prolonged unchecked states of stress, whether ‘eu-stress’ or ‘distress’, can become wearing if unchecked or not acknowledged and constructively managed. Some stressors are controllable, others are not. The key appears to hinge on awareness of the cause and consequence of the stressor and the state of ‘”being” in stress’, and the individuals attitude and positive proactive response; supportive and/or preventative measures can then be taken.

Prolonged unchecked states of stress, whether ‘eu-stress’ or ‘distress’, can become wearing if unchecked or not acknowledged and constructively managed. Some stressors are controllable, others are not. The key appears to hinge on awareness of the cause and consequence of the stressor and the state of ‘”being” in stress’, and the individuals attitude and positive proactive response; supportive and/or preventative measures can then be taken.

Smith et al (2012) identify the following factors which may influence an individual’s stress tolerance:

The Department of Work and Pensions (2010) list various ways in which employers can support employee’s wellbeing at work. Suggestions include ‘access to counselling or employee assistance programmes’, ‘access to occupational health’, ‘free or subsidised gym membership’, ‘fitness classes at work’. Other supportive measures might also include:

Offering in-house services or subsidies toward support might improve employee’s perception, attitude and experience of their work and their work environment and may reduce time off work through illness, saving money for the employer. Aromatherapy, for example, offers a valuable stress management resource and could be delivered as an aspect of ‘access to occupational health provision’ or an ‘employee assistance programme’. Aromatherapy provides both physiological and psycho-emotional support and is most suitable for stress and stress related conditions.

To test the potential of Aromatherapy as a work-based stress management tool, an in-house clinic was set up for members of staff at the University (located in the North of England). At the time, the University was engaged in a programme of reconfiguration, which impacted on job roles and team structures. The Aromatherapy Clinic was temporarily organised to support staff through this process of change and to evaluate the level of interest and the potential value of continuing to provide such in-house wellbeing support in future.

To test the potential of Aromatherapy as a work-based stress management tool, an in-house clinic was set up for members of staff at the University (located in the North of England). At the time, the University was engaged in a programme of reconfiguration, which impacted on job roles and team structures. The Aromatherapy Clinic was temporarily organised to support staff through this process of change and to evaluate the level of interest and the potential value of continuing to provide such in-house wellbeing support in future.

The Aromatherapy Clinic was available on Mondays and ran for a period of twelve weeks. An email was sent to members of staff informing them of the service; appointments slots were quickly filled and there was no need to re-advertise during the twelve week period. Treatments consisted of a full body massage applying a personalised blend of essential oils. Clients signed a ‘Consent to Treatment’ and a ‘Consent to Research’ form (requesting permission to use anonymous data collected through a post treatment questionnaire; treatment did not depend on participation) prior to commencement of their treatment. Although there was some adaptation to the massage routine (for example, some clients did not want their abdomen massaging, some did not want their head massaging etc.) the massage techniques and sequence applied remained as consistent as possible. However, because client’s participated in the selection of essential oils for their treatment, no client had exactly the same blend as odour preferences varied from client to client, even if presenting with similar symptoms.

Fifteen to thirty minutes were allocated to consultation and preparation for massage (half an hour for first appointments, fifteen minutes for subsequent appointments). Full body massage took approximately one hour to complete. Recovery, dressing and aftercare advice took fifteen to twenty minutes – each treatment lasted one hour and forty five minutes to two hours. Consultation is a significant aspect of treatment, guarding treatment integrity to ensure that clients are not contra-indicated, ensuring clients fully understand the process and that an appropriate remedy is prescribed; the therapist is able glean information with which to hone essential oil blends to meet client’s specific needs. Clients paid a token fee for their treatments to cover costs (essential oils, carrier oils, laundry etc.).

The majority of clients cited their reason for seeking treatment as a need to distress, to relax, to manage change and to improve their overall wellbeing. Some clients had other related background conditions such as IBS, insomnia, asthma and muscle tension in the lumber, upper thoracic and cervical region of the back and neck; a pattern of muscle tension and postural problems consistent with sitting and working at a desk was observed.

All clients were female. Their ages ranged between 26 and 65 years old; 42% aged between 36 and 45 years old, 25% aged between 56 and 65 years old.

84% of the clients agreed that their treatments met with their expectation. For example, “wonderful relaxing experience”, “really well prepared and excellent treatment”, “very good”; one client stated that the “environment [was] a little odd because at uni”.

All clients received full body massage; some were given a roller bottle containing the essential oil blend used during massage to use at home.

100% of the clients agreed that their symptoms improved during and post treatment. For example, “I felt relaxed and muscles tensions were eased”, “I felt perkier after the treatment”, “felt more relaxed and less stressed after both sessions”, “really felt the benefits and slept better that night”, “pain relief for rest of day, felt very relaxed for rest of day”.

On a scale of 1 to 10 (1 = no difference in symptoms 10 = symptoms completely cleared), clients scored between 5 and 10 in their Post Treatment Diary up to a week after their treatments.

The majority of clients agreed that they liked the smell of their essential oil blend. However, one client did not like the after-smell, or dry-out odour (see odour profile chart), of one of her essential oils (Spikenard Nardostachys jatamansi).

100% of the clients agreed that they would book aromatherapy treatments again; 50% agreed they would book once a month, 25% once a week to once a fortnight. Other comments made:

Although clients were given a range of essential oils to choose from, Frankincense (Boswellia carterii) and Cypress (Cupressus sempervirens)appeared most frequently in blends selected. Interestingly, Frankincense is indicated for anxiety, nervous tension and depression, stress, fear of the future and indecision. Frankincense also slows breathing to produce a calm, soothing, elevated mental state, bringing a sense of peace. Cypress is indicated for nervous tension, stress related conditions, debility, lack of concentration, bereavement, uncontrolled crying and talking, and as aiding transition. Other essential oils selected included Carrot Seed (Duacus carota), Cedarwood (Cedrus Atlantica, Cedrus Hymalayan), Rose Geranium (Pelargonium roseum), Lime (Citrus aurantifolia), Mandarin (Citrus reticulata Blanco), Petitgrain (Citrus x autrantium) and Rose (Rosa centifolia) all of which are indicated as having immune stimulating properties. Considering the psycho-emotional and physiological effects of stress (see appendix) in correlation with client’s personal selection of certain odours, validation of the therapeutic properties attributed can be observed (see Therapeutic properties of main chemicals groups in essential oils used). (Battaglia 2002; Lawless 1996; Sheppard-Hanger 1995)

Although clients were given a range of essential oils to choose from, Frankincense (Boswellia carterii) and Cypress (Cupressus sempervirens)appeared most frequently in blends selected. Interestingly, Frankincense is indicated for anxiety, nervous tension and depression, stress, fear of the future and indecision. Frankincense also slows breathing to produce a calm, soothing, elevated mental state, bringing a sense of peace. Cypress is indicated for nervous tension, stress related conditions, debility, lack of concentration, bereavement, uncontrolled crying and talking, and as aiding transition. Other essential oils selected included Carrot Seed (Duacus carota), Cedarwood (Cedrus Atlantica, Cedrus Hymalayan), Rose Geranium (Pelargonium roseum), Lime (Citrus aurantifolia), Mandarin (Citrus reticulata Blanco), Petitgrain (Citrus x autrantium) and Rose (Rosa centifolia) all of which are indicated as having immune stimulating properties. Considering the psycho-emotional and physiological effects of stress (see appendix) in correlation with client’s personal selection of certain odours, validation of the therapeutic properties attributed can be observed (see Therapeutic properties of main chemicals groups in essential oils used). (Battaglia 2002; Lawless 1996; Sheppard-Hanger 1995)

This survey appears to indicate that essential oils, combined with massage and the positive effects of intentionally caring touch (Buckle 2007), may offer significant support for stress and stress related conditions, Essential oils do appear to ‘liven’ the brain (Maury 1961). Neural messages, instigated through touch and the olfaction of essential oils, appear to encourage a state of calm and relaxation, potentially providing relief from chronic pain, through stimulation of the release of endorphins and enkaphalins (Buckle 2007; Tisserand 1997; Maury 1961). In this state, the body seems better able to function, as Maury (1961) suggests:

“Contrary to popular belief, relaxation is not a sate of inertia. The disappearance of all contractions and muscular tensions frees energy, and the whole attention of the individual is eminently “alert” and conscious.……… If the individual is adequately relaxed and has transposed all his freed energy on the mental plan, ideas, memories (and the precision of the latter) become extremely sharp. Details which seemed unimportant rise to the memory, details which the individual is unaware that he ever recorded. Everything transpires as if part of the brain, having been out of the circuit in normal conditions, suddenly began to function.”

Indeed, all clients said their symptoms improved and that they felt more relaxed. Sometimes clients felt sleepy after their aromatherapy massage, however, this was usually because these clients arrived feeling tired and ‘burned out’ and needed to sleep to restore their energy; once refreshed, they reported a surge of energy and a sense of feeling uplifted post treatment.

Essential oils are highly concentrated, volatile, odiferous chemical derivatives extracted from plants, trees, roots, grasses, flowers, fruits and shrubs. As well as smelling very pleasant, essential oils posses many qualities. For example, most are anti-septic, but some are especially powerful, e.g. Thymus vulgaris (Thyme), Lavendula spika, Lavendula stoechas (Lavender) and Eucalyptus globulus (Eucalyptus). Some have anti-viral qualities, e.g. Melaleuca quinquenervia var. cineol (Niaouli 1,8 cineole type), Cinnamom zeylanicum (Cinnamon) and Eugenia caryophyliate (Clove bud). Some have anti-spasmodic qualities, e.g. Helichrysum italicum (Helichrysum) and foeniculum vulgare (Fennel), Origanum marjorana(Marjoram). Some essential oils also have powerful immune stimulating qualities, e.g. Melaleuca alternifolia (Tea Tree), Ravensara aromatica(Ravensara). Some act as skin healing (cicatrizant) agents, e.g. Pogostemom cablin (Patchouli), Daucus carrota ssp maximus (Carrot Seed), Chamaemelum nobile (Chamomile Roman). (Godfrey 2011, 2009; Hoare 2010; Buckle 2007; Battaglia 2006; Minga 2002; Beshara 2002; Alexander 2000; Sorensen 2000; Sheppard-Hanger 2000; Tisserand 1997; Imberger et al 1993; Valnet 1980; Gattefosé 1937)

“Essential oils are very effective in treating small to medium wounds, skin abrasions, excoriations, skin infections and other topical health problems providing an appropriate concentration of essential oil is used”. (Kerr 2002)

(NB essential oils should only be prescribed and used in this way by trained health care practitioners)

Aromatherapy generally combines the tactile medium of touch, through massage, with the use of essential oils to engender a state of deep relaxation that potentially serves to enhance a sense of peace and well being within the recipient, while at the same time improving immunological homeostasis and restoring available energy. Essential oils may also be applied topically in gels, ointment and compresses to treat local conditions, such as eczema, sprains, insect bites and improve scar tissue and are also applied using none tactile methods of application, such as, for example, vaporisation (room diffuser and/or tissues), aroma sticks (nasal inhalers), ‘therapeutic perfumes’ and steam inhalation. (Buckle 2007; Besouilah & Buck 2006; Sheppard-Hanger 1995)

Aromatherapy massage assists the absorption of essential oils into the epidermis (skin) and soft tissue below the surface where minute chemical components from the essential oils are absorbed and transported via the circulatory system through the body’s various organs. The action of massage warms surface tissue, improves circulation, gently stimulates the nervous system and relieves muscle tension. Aromatherapy massage involves deliberate, focused movements yet does not over stimulate, which affords an opportunity for the client to completely relax, potentially encouraging the body’s self healing and natural regulating mechanisms to engage, supporting immunity, wellness and a sense of wellbeing. (Hoare 2010; Salvo 2003; Tisserand 1997)

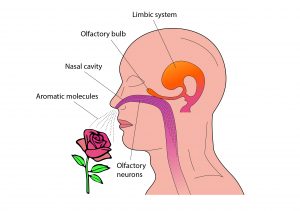

When inhaled, or absorbed, via the olfactory system (nose -lungs), essential oils appear to work most profoundly on the limbic system, an area within the brain known also as the ‘emotional brain’.

Molecules of essential oils carried by the inward breath reach the olfactory bulb at the top of the nose, where minute hair-like receptors transfer neural messages between the olfactory system and the limbic area of the brain (hypothalamus, hippocampus, temporal cortex, amygdale and other limbic structures), potentially exerting an influence on mood, memory storage, emotion, behaviour and immunity. For example, someone who is anxious or nervous may feel calmed and relaxed by the odoriferous inhalation of Spikenard (Nardostachys jatamansi) or perhaps Chamomile Roman (Anthemis nobilis) and someone who is depressed may feel uplifted in the same way when inhaling Bergamot (Citrus bergamia) or Neroli (Citrus bergamia), and so on. The odour profile of each essential oil can be said to have a unique ‘personality’, which the recipient will respond to according to their perception of that odour. (Whitfeild & Greenfield 1997; Sheppard-Hanger 1995; Damian 1995)

Molecules of essential oils carried by the inward breath reach the olfactory bulb at the top of the nose, where minute hair-like receptors transfer neural messages between the olfactory system and the limbic area of the brain (hypothalamus, hippocampus, temporal cortex, amygdale and other limbic structures), potentially exerting an influence on mood, memory storage, emotion, behaviour and immunity. For example, someone who is anxious or nervous may feel calmed and relaxed by the odoriferous inhalation of Spikenard (Nardostachys jatamansi) or perhaps Chamomile Roman (Anthemis nobilis) and someone who is depressed may feel uplifted in the same way when inhaling Bergamot (Citrus bergamia) or Neroli (Citrus bergamia), and so on. The odour profile of each essential oil can be said to have a unique ‘personality’, which the recipient will respond to according to their perception of that odour. (Whitfeild & Greenfield 1997; Sheppard-Hanger 1995; Damian 1995)

Research has shown that certain essential oils may stimulate and balance the regulation of hormone release (e.g. Vitex agnus castus (Chaste Tree), Lavendula angustifolia (Lavender) and citrus limonene (Lemon)), potentially exerting a positive influence on mood (stimulating or sedating the recipient), emotion and even mental alertness (Sorensen, 2001; Williams, 2000; Alexander, 2000; Damian, 1995; Buchbauer et al, 1992).

“The psychoactive effects of essential oils are recordable by electroencepholgram (EEG) measurements showing brain wave amplitude and frequency. Odors produce cortical brain-wave (EEG) activity responses involving alpha, beta, delta and theta waves……………..jasmine increases alertness and attention by stimulating beta brain-wave activity……..the sedative effects of Lavender were also demonstrated, measured by EEG and CNV amplitude.” (Damian 1995)

Due to this cephalic influence, Aromatherapy has also proved effective when used complementarily with other modilities such as, for example, counselling, behavioural and emotional therapy.

Aromatherapy, consequently, is ideal for conditions related to stress and anxiety, and for some minor stress related chronic conditions such as, for example, minor depression, irritable bowel syndrome, certain skin conditions, premenstrual syndrome, menopausal symptoms, to name just a few. Inhalation of essential oils may also assist the elimination of colds and ‘flu. Equally, the general antiseptic and immune stimulant qualities of some essential oils render Aromatherapy as an ideal preventative therapy too. Even though essential oils may be chosen for a specific condition, their complex chemical structure means that they have multiple therapeutic attributes which work at one and the same time. Buckle (2007), for example, observes that a client who is attracted to the odour of lemongrass for its sedative effects may benefit at the same time from this oil’s anti-fungal properties when adding it to a foot bath prescribed for relaxation where the client is contraindicated for massage. Buckle uses this example to illustrate the anomaly of professional boundaries, where an aromatherapist cannot prescribe essential oils as ‘medication’ but may consequently alleviate other symptoms even though the intention of treatment is to relieve stress and/or to aid relaxation (Godfrey 2011).

The Staff Aromatherapy Stress Clinic was received well by members of staff who indicated that they valued this service and would continue to use it if it were available to them in future. All clients appeared to benefit from their treatments. The combination of massage with the therapeutic application of essential oils appeared to provide an effective method of managing stress and aiding relaxation. Offering in-house Aromatherapy treatments might improve staff productivity and support a positive attitude toward work, improve the work environment, and, perhaps reduce absence through stress related illness.